26 May Wild Bear Lodge in the FT

By Mike Carter

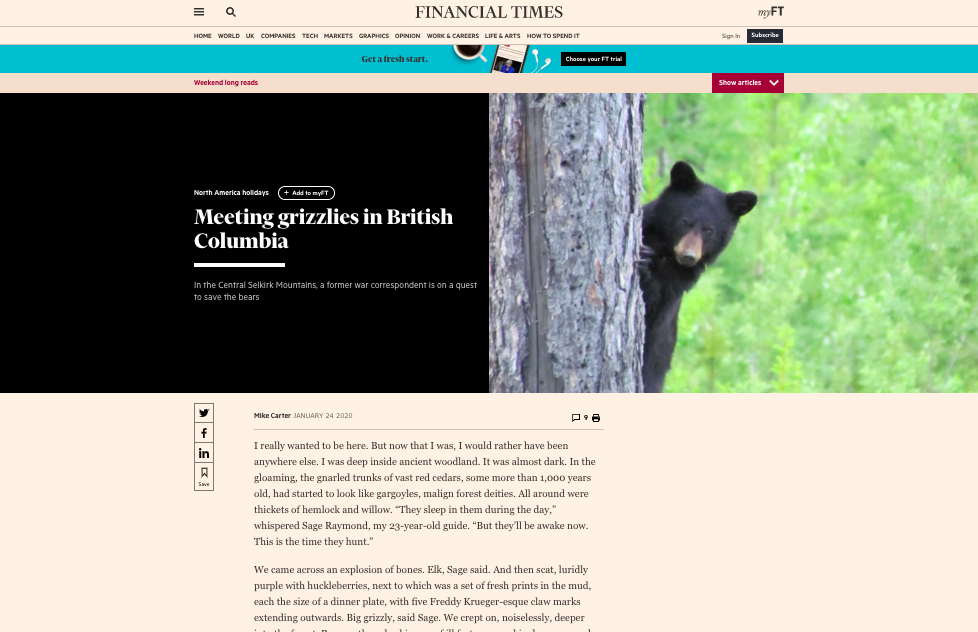

I really wanted to be here. But now that I was, I would rather have been anywhere else. I was deep inside ancient woodland. It was almost dark. In the gloaming, the gnarled trunks of vast red cedars, some more than 1,000 years old, had started to look like gargoyles, malign forest deities. All around were thickets of hemlock and willow. “They sleep in them during the day,” whispered Sage Raymond, my 23-year-old guide. “But they’ll be awake now. This is the time they hunt.”

We came across an explosion of bones. Elk, Sage said. And then scat, luridly purple with huckleberries, next to which was a set of fresh prints in the mud, each the size of a dinner plate, with five Freddy Krueger-esque claw marks extending outwards. Big grizzly, said Sage. We crept on, noiselessly, deeper into the forest. Ravens, those harbingers of ill fortune, mockingly caw-cawed us from the branches above.

From a tangle of dogwood, there came a rustle. Sage felt for the can of pepper spray on her belt. The rustle became a crash, and then an eruption of noise, hissing and drumming, the sound of a heavy, charging animal, and coming straight at us. It burst out: a ruffed grouse. “We call that the heart-attack bird,” laughed Sage. It was almost the last thing I ever heard.

I was in the Central Selkirk Mountains, southern British Columbia, a 450-mile drive inland from Vancouver. I was staying at the Wild Bear Lodge, six wooden cabins by the foaming Lardeau river at the bottom of a steep valley, about an hour’s drive from Kaslo, the nearest small town.

The six cabins of the Wild Bear Lodge by the Lardeau river, about an hour’s drive from the nearest town Kaslo

It was here in 2005 that Briton Julius Strauss, 52, and his Estonian wife, Kristin, 43, had first pitched up. Julius had spent years working as a war correspondent for a British newspaper, covering bloody conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Sierra Leone. After reporting from the Beslan school siege in Russia in 2004, where more than 330 people died, including 186 children, Julius had taken time out, suffering from PTSD and on antidepressants.

While driving across Canada, the couple had found this remote spot, teeming with grizzlies, and decided to buy the property. Needing to earn a living, Julius had trained as a bear guide — the first fully qualified bear guide in Interior British Columbia — still spending his days among lethal predators, but these ones armed with razor-sharp claws, not AK-47s.

The day after my near heart failure, I went out again, this time with Julius, climbing high through the spruce and the larch, stopping to retrieve the memory cards from camera traps. Julius popped one into his tablet to see what had been through. On the film, cougars and coyotes padded past, and one immense gangly moose with a candelabrum of antlers on its head. And then a big grizzly, a female, followed by three cubs, two staying close to mum, the third always straying off into the brush before being called back with a huff from its mother.

The bear stopped opposite the camera at a rubbing tree, where grizzlies leave scent trails to communicate with other bears, stood on her hind legs so she was 7ft tall, and shook her entire booty with such gleeful abandon that she looked like a drunken aunt dancing to Beyoncé at a wedding.

We climbed higher, into the snow, and a superhighway of animal tracks. Julius pointed out wolves and snowshoe hares and, of course, bears. From the prints he could tell how big the animals were, in which direction they were heading, even at what speed they were moving, thus indicating flight or pursuit.

“In Britain, we’ve killed all the big animals,” Julius said. “Here, where you live closely with things that can kill you, you start sniffing the air, watching the tracks, moving and listening in a different way. I think it’s how we evolved. It feels like a primal connection.”

There was nothing too primal about evenings at Wild Bear Lodge. Gathering in Julius and Kristin’s beautiful home, with its log fire, we ate pork tenderloin stuffed with goat’s cheese, spinach and pine nuts or risotto made with locally picked morel mushrooms. All of the vegetables and salads and herbs used were either grown by Kristin, a formally trained chef, or sourced locally. The water came from a well, most of the power was solar and heating was via the wood-burning stoves in the cabins. “We hope within three years that all our vehicles will be electric, too,” said Julius.

Next day we rafted down the Lardeau, where the mist hung heavy in the temperate rainforest, making it look as if it were smouldering after a fire. Bald eagles watched us pass, serenading us with their high-pitched shriek, like car alarms going off. Mergansers and dippers plopped and splashed, as we steered between tangles of huge tree trunks, dumped like toothpicks when the river was in spate, the origin of the word logjam. All the time, we kept our eyes peeled on the bankside willow thickets, looking for bears. But in vain. Julius explained how they had learnt over time to emerge only in the crepuscule or at night, to avoid human hunters who had devastated their numbers.

So it was that as the sun started to set behind the Selkirks, we headed out once more. We walked along the bank of the Lardeau and sat down in the mud behind a fallen tree. And waited. In the shallow, pellucid waters we watched the macabre autumnal death pageant of the sockeye salmon, thousands and thousands of them, like crimson glow sticks, lolling and flopping, waiting to spawn before expiring. The fish have been landlocked since the last Ice Age cut off their route to the ocean. But still they act out their ancient migratory drama.

From a few hundred yards up river, on the far bank, there was a loud crashing noise. I looked through my binoculars. It was a large grizzly bear, with three cubs in tow. The same ones from the camera trap, Julius said. And sure enough, the smallest of the cubs was falling off branches, always hanging back, disappearing into the scrub, getting a reprimand from its mum, the other cubs happily squabbling. The family moved ever closer to us, now perhaps only 100 yards away across the shallow river. Then directly opposite us, 40 yards away, so close that I didn’t need the binoculars any more. I could hear her breath, amplified over the narrow stretch of water, see her terrifying claws glinting white in the gloom, as she idly scooped a salmon out of the river and tore its head off, feasting on the brain, sheathed in fat, ideal for these hyperphagic bears, gorging themselves to survive their impending hibernation.

The epiphytes dangling from the trees wafted gently in the breeze. The huge grizzly was now downwind of us. Julius removed the spray can from his belt. The mother sniffed the air and started huffing like a steam train. Then she slowly turned her head and looked me straight in the eye. My heart felt like it would burst out of my chest. In seconds, I had gone from watching grizzly bears through a lens, as if on some TV nature documentary, to being in the film, and as prey. Time stopped. Finally, she gathered her cubs and disappeared into the scrub.

“That’s exactly what we offer,” said Julius, on the drive back to the lodge. “Taking an uncontrolled environment and allowing people to experience it in a controlled way, mitigating most of the risks but still feeling the benefits. That animal could easily disembowel you. But it doesn’t. I like the humility that induces. It puts man back on his toes, his rightful natural place.”

I spent the next few days walking with Julius, out on the trails, up on our toes, learning more about grizzly bears and their lives. Julius told me about the first bear he’d met, soon after arriving, when finances were precarious and the couple was unsure whether they could survive. She was called Apple, after the fruit she liked to gorge on, often so stuffed she could barely move. “She was a good teacher,” Julius said. “I learned to watch the position of her ears, the subtle opening and closing of her mouth, the stiffness of her body posture; all indicators of mood and intent. We watched her stride like a monarch on the dirt road next to the ranch.”

One day, in 2015, Apple was shot dead, totally legally, by a trophy hunter, leaving two yearling cubs to fend for themselves. At that time, nearly 300 bears were shot annually in British Columbia. Julius and Kristin were devastated and decided to act. “Grizzly bear hunting was worth C$2m a year to the BC economy,” Julius told me. “Whereas bear-watching was worth C$30m and rising. Also, 90 per cent of province residents opposed the killing of grizzlies.” After much lobbying of politicians, a group led by Julius finally got a total ban enacted in December 2017.

It seemed fitting that Julius, witness to so much human misery, had found his place here, a place where he had actually been able to stop man killing. So much for saving bears, but what impact had the place had on him?

“If your days are filled with blood and suffering and interviewing victims of torture, you’re going to internalise that,” he said, bending down to inspect grizzly tracks in the snow, and talking about his plans to bring military veterans here to help them overcome PTSD. “In the end, it was nature that cured me. It took a long time, but I am as well as I’ll ever be.”

On my last day, in the encroaching gloom, we returned to the river, wending our way through the dark forest once more, on our toes. In a few short weeks, the brutal Canadian winter would arrive and the bears would be asleep. “I still walk these trails alone then, but there are no bears. Nothing can go wrong in that way,” said Julius. “Until spring, the world gets a little bit greyer somehow. I miss them.”

At the river, the light almost completely gone, a large male bear emerged from the bushes opposite us and paddled out into midstream, barely 30 yards away, just an enormous shadow really, splashing and huffing, the sounds getting closer and closer, every noise, every crack of a branch, somehow amplified, all my senses on hyper alert. I remembered what Julius had told me back at the lodge, about his time in war zones, how he’d always wanted to be in the middle of the action, and yet when he’d got there how afraid he’d felt. Afraid yet fully alive.

Finally, the bear disappeared into the thick red osier dogwood on the far bank and was gone. I looked at Julius and my fellow guests. Everybody was beaming. Everybody was on their toes.

Sign up for The Grizzly Bear Diaries